Blog Archive

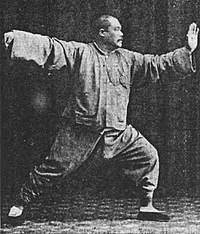

Yang Chengfu in a posture from the Yang style tai chi chuan solo form known as Single Whip c. 1931 | |

| Also known as | t'ai chi ch'üan; taijiquan |

|---|---|

| Focus | Hybrid |

| Hardness | Forms competition, light-contact (pushing hands, no strikes), full contact (striking, kicking, throws, etc.) |

| Country of origin | China |

| Creator | Disputed |

| Famous practitioners | Chen Wangting, Chen Changxing, Yang Lu-ch'an, Wu Yu-hsiang, Wu Ch'uan-yu, Wu Chien-ch'uan, Sun Lu-t'ang, Yang Chengfu, Chen Fake, Wang Pei-sheng |

| Parenthood | Tao Yin |

| Olympic sport | Demonstration only |

| Tai chi chuan | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 太極拳 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 太极拳 | ||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | supreme ultimate fist | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| | This article contains Chinese text. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Chinese characters. |

| Part of the series on Chinese martial arts |

|

| List of Chinese martial arts |

|---|

| Terms |

| Historical places |

|

| Historical people |

|

| Related |

Tai chi chuan (simplified Chinese: 太极拳; traditional Chinese: 太極拳; pinyin: tàijíquán; Wade-Giles: t'ai4 chi2 ch'üan2) (literal translation "Supreme Ultimate Fist") is an internal Chinese martial art often practiced for health reasons. It is also typically practiced for a variety of other personal reasons: its hard and soft martial art technique, demonstration competitions, and longevity. Consequently, a multitude of training forms exist, both traditional and modern, which correspond to those aims. Some of tai chi chuan's training forms are well known to Westerners as the slow motion routines that groups of people practice together every morning in parks around the world, particularly in China.

Today, tai chi has spread worldwide. Most modern styles of tai chi trace their development to at least one of the five traditional schools: Chen, Yang, Wu/Hao, Wu and Sun.

Overview

The term t'ai chi ch'uan literally translates as "supreme ultimate fist", "boundless fist," "great extremes boxing", or simply "the ultimate" (note that 'chi' in this instance is the Wade-Giles version of the Pinyin jí, not to be confused with the use of ch'i / qì in the sense of "life-force" or "energy"). The concept of the Taiji "supreme ultimate" appears in both Taoist and Confucian Chinese philosophy where it represents the fusion or mother[1] of Yin and Yang into a single ultimate, represented by the Taijitu symbol. Thus, tai chi theory and practice evolved in agreement with many of the principles of Chinese philosophy including both Taoism and Confucianism. Tai chi training first and foremost involves learning solo routines, known as forms (套路 taolu). While the image of tai chi chuan in popular culture is typified by exceedingly slow movement, many tai chi styles (including the three most popular, Yang, Wu and Chen) have secondary forms of a faster pace. Some traditional schools of tai chi teach partner exercises known as pushing hands, and martial applications of the postures of the form.The art received its name when Ong Tong He, a scholar in the Imperial Court, witnessed Yang Lu Chan ("Unbeatable Yang") demonstrate. Ong wrote: 'Hands holding Taiji shakes the whole world, a chest containing ultimate skill defeats a gathering of heroes.'

Tai chi chuan is generally classified as a form of traditional Chinese martial arts of the Neijia (soft or internal) branch. It is considered a soft style martial art — an art applied with internal power — to distinguish its theory and application from that of the hard martial art styles.[2]

Since the first widespread promotion of tai chi's health benefits by Yang Shaohou, Yang Chengfu, Wu Chien-ch'uan and Sun Lutang in the early twentieth century,[3] it has developed a worldwide following among people with little or no interest in martial training, for its benefit to health and health maintenance.[4] Medical studies of tai chi support its effectiveness as an alternative exercise and a form of martial arts therapy.

Focusing the mind solely on the movements of the form purportedly helps to bring about a state of mental calm and clarity.[citation needed] Besides general health benefits and stress management attributed to tai chi training, aspects of traditional Chinese medicine are taught to advanced tai chi students in some traditional schools.[5]

Some martial arts, especially the Japanese martial arts, require students to wear a uniform during practice. Tai chi chuan schools do not generally require a uniform, but both traditional and modern teachers often advocate loose, comfortable clothing and flat-soled shoes.[6][7]

The physical techniques of tai chi chuan are described in the tai chi classics, a set of writings by traditional masters, as being characterized by the use of leverage through the joints based on coordination and relaxation, rather than muscular tension, in order to neutralize or initiate attacks.[citation needed] The slow, repetitive work involved in the process of learning how that leverage is generated gently and measurably increases, opens the internal circulation (breath, body heat, blood, lymph, peristalsis, etc.)[citation needed]

The study of tai chi chuan primarily involves three aspects[citation needed]:

- Health: An unhealthy or otherwise uncomfortable person may find it difficult to meditate to a state of calmness or to use tai chi as a martial art. Tai chi's health training therefore concentrates on relieving the physical effects of stress on the body and mind. For those focused on tai chi's martial application, good physical fitness is an important step towards effective self-defense.

- Meditation: The focus and calmness cultivated by the meditative aspect of tai chi is seen as necessary in maintaining optimum health (in the sense of relieving stress and maintaining homeostasis) and in application of the form as a soft style martial art.

- Martial art: The ability to use tai chi as a form of self-defense in combat is the test of a student's understanding of the art. Martially, Tai chi chuan is the study of appropriate change in response to outside forces; the study of yielding and "sticking" to an incoming attack rather than attempting to meet it with opposing force[8]. The use of tai chi as a martial art is quite challenging and requires a great deal of training.[9]

History and styles

See also: History of Chinese Martial Arts

There are five major styles of tai chi chuan, each named after the Chinese family from which it originated:- Chen style (陳氏) of Chen Wangting (1580–1660)

- Yang style (楊氏) of Yang Lu-ch'an (1799-1872)

- Wu or Wu/Hao style (武氏) of Wu Yu-hsiang (1812-1880)

- Wu style (吳氏) of Wu Ch'uan-yu (1834–1902) and his son Wu Chien-ch'uan (1870-1942)

- Sun style (孫氏) of Sun Lu-t'ang (1861–1932)

There are now dozens of new styles, hybrid styles, and offshoots of the main styles, but the five family schools are the groups recognized by the international community as being the orthodox styles. Other important styles are Zhaobao Tai Chi, a close cousin of Chen style, which has been newly recognized by Western practitioners as a distinct style, and the Fu style, created by Fu Chen Sung, which evolved from Chen, Sun and Yang styles, and also incorporates movements from Pa Kua Chang.

All existing styles can be traced back to the Chen style, which had been passed down as a family secret for generations. The Chen family chronicles record Chen Wangting, of the family's 9th generation, as the inventor of what is known today as Tai Chi. Yang Lu-ch'an became the first person outside the family to learn Tai Chi. His success in fighting earned him the nickname "Unbeatable Yang", and his fame and efforts in teaching greatly contributed to the subsequent spreading of Tai Chi knowledge.

When tracing tai chi chuan's formative influences to Taoist and Buddhist monasteries, there seems little more to go on than legendary tales from a modern historical perspective, but tai chi chuan's practical connection to and dependence upon the theories of Sung dynasty Neo-Confucianism (a conscious synthesis of Taoist, Buddhist and Confucian traditions, especially the teachings of Mencius) is claimed by some traditional schools.[2] Tai chi's theories and practice are believed by these schools to have been formulated by the Taoist monk Zhang Sanfeng in the 12th century, at about the same time that the principles of the Neo-Confucian school were making themselves felt in Chinese intellectual life.[2] However, modern research casts serious doubts on the validity of those claims, pointing out that a 17th century piece called "Epitaph for Wang Zhengnan" (1669), composed by Huang Zongxi (1610-1695 A.D.) is the earliest reference indicating any connection between Zhang Sanfeng and martial arts whatsoever, and must not be taken literally but must be understood as a political metaphor instead. Claims of connections between Tai Chi and Zhang Sanfeng appear no earlier than the 19th century. [10]

Family trees

These family trees are not comprehensive. Names denoted by an asterisk are legendary or semi-legendary figures in the lineage; while their involvement in the lineage is accepted by most of the major schools, it is not independently verifiable from known historical records. The Cheng Man-ch'ing and Chinese Sports Commission short forms are derived from Yang family forms, but neither are recognized as Yang family tai chi chuan by standard-bearing Yang family teachers. The Chen, Yang and Wu families are now promoting their own shortened demonstration forms for competitive purposes.Legendary figures

| Zhang Sanfeng* c. 12th century NEIJIA | |||||||

| | | | | | |||

| Wang Zongyue* 1733-1795 | |||||||

Five major classical family styles

| Chen Wangting 1580–1660 9th generation Chen CHEN STYLE | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| | | | | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | ||||||||||||||||||

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chen Changxing 1771–1853 14th generation Chen Chen Old Frame | | | | | | | | | | | | | | Chen Youben c. 1800s 14th generation Chen Chen New Frame | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | ||||||||||||||||||

| Yang Lu-ch'an 1799–1872 YANG STYLE | | | | | | | | | | | | | | Chen Qingping 1795–1868 Chen Small Frame, Zhaobao Frame | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | ||||||||||||||||||

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yang Pan-hou 1837–1892 Yang Small Frame | | | | | | Yang Chien-hou 1839–1917 | | | | | | Wu Yu-hsiang 1812–1880 WU/HAO STYLE | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |||||||||||||||

| | | | | | | | | | | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wu Ch'uan-yu 1834–1902 | | Wang Jaio-Yu 1836-1939 Original Yang | | Yang Shao-hou 1862–1930 Yang Small Frame | | Yang Ch'eng-fu 1883–1936 Yang Big Frame | | Li I-yü 1832–1892 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | ||||||||||||||||

| Wu Chien-ch'üan 1870–1942 WU STYLE 108 Form | | Kuo Lien Ying 1895–1984 | | | | | | Yang Shou-chung 1910–85 | | Hao Wei-chen 1849–1920 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | ||||||||||||||||||

| Wu Kung-i 1900–1970 | | | | | | | | | | | | | | Sun Lu-t'ang 1861–1932 SUN STYLE | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | ||||||||||||||||||

| Wu Ta-k'uei 1923–1972 | | | | | | | | | | | | | | Sun Hsing-i 1891–1929 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

[edit] Modern forms

| Yang Ch`eng-fu | |||||||||||||||

| | | | | | | | | | | ||||||

| | | | | | |||||||||||

| Cheng Man-ch'ing 1901–1975 Short (37) Form | | Chinese Sports Commission 1956 Beijing 24 Form | |||||||||||||

| | | | | | | | | | |||||||

| | | | | 1989 42 Competition Form (Wushu competition form combined from Sun, Wu, Chen, and Yang styles) | |||||||||||

Training and techniques

As the name "tai chi chuan" is held to be derived from the Taiji symbol (Taijitu or T'ai chi t'u, 太極圖), commonly known in the West as the "yin-yang" diagram, tai chi chuan is therefore said in literature preserved in its oldest schools to be a study of yin (receptive) and yang (active) principles, using terminology found in the Chinese classics, especially the Book of Changes and the Tao Te Ching.[2]The core training involves two primary features: the first being the solo form (ch'üan or quán, 拳), a slow sequence of movements which emphasize a straight spine, abdominal breathing and a natural range of motion; the second being different styles of pushing hands (tui shou, 推手) for training movement principles of the form in a more practical way.

The solo form should take the students through a complete, natural range of motion over their center of gravity. Accurate, repeated practice of the solo routine is said to retrain posture, encourage circulation throughout the students' bodies, maintain flexibility through their joints, and further familiarize students with the martial application sequences implied by the forms. The major traditional styles of tai chi have forms which differ somewhat cosmetically, but there are also many obvious similarities which point to their common origin. The solo forms, empty-hand and weapon, are catalogs of movements that are practiced individually in pushing hands and martial application scenarios to prepare students for self-defense training. In most traditional schools, different variations of the solo forms can be practiced: fast–slow, small circle–large circle, square–round (which are different expressions of leverage through the joints), low sitting/high sitting (the degree to which weight-bearing knees are kept bent throughout the form), for example.

Two Western students receive instruction in Pushing hands, one of the core training exercises of tai chi

Tai chi's martial aspect relies on sensitivity to the opponent's movements and center of gravity dictating appropriate responses. Effectively affecting or "capturing" the opponent's center of gravity immediately upon contact is trained as the primary goal of the martial tai chi student.[5] The sensitivity needed to capture the center is acquired over thousands of hours of first yin (slow, repetitive, meditative, low impact) and then later adding yang ("realistic," active, fast, high impact) martial training through forms, pushing hands, and sparring. Tai chi trains in three basic ranges: close, medium and long, and then everything in between. Pushes and open hand strikes are more common than punches, and kicks are usually to the legs and lower torso, never higher than the hip, depending on style. The fingers, fists, palms, sides of the hands, wrists, forearms, elbows, shoulders, back, hips, knees and feet are commonly used to strike, with strikes to the eyes, throat, heart, groin and other acupressure points trained by advanced students. Joint traps, locks and breaks (chin na) are also used. Most tai chi teachers expect their students to thoroughly learn defensive or neutralizing skills first, and a student will have to demonstrate proficiency with them before offensive skills will be extensively trained. There is also an emphasis in the traditional schools that one is expected to show wu te (武德), martial virtue or heroism, to protect the defenseless and show mercy to one's opponents.[3]

In addition to the physical form, martial tai chi chuan schools also focus on how the energy of a strike affects the other person. Palm strikes that physically look the same may be performed in such a way that it has a completely different effect on the target's body. A palm strike that could simply push the opponent backward, could instead be focused in such a way as to lift the opponent vertically off the ground breaking their center of gravity; or it could terminate the force of the strike within the other person's body with the intent of causing internal damage.

Other training exercises include:

- Weapons training and fencing applications employing the straight sword known as the jian or chien or gim (jiàn 劍), a heavier curved sabre, sometimes called a broadsword or tao (dāo 刀, which is actually considered a big knife), folding fan also called san, wooden staff (2m. in length) known as kun (棍), 7 foot (2 m) spear and 13 foot (4 m) lance (both called qiāng 槍). More exotic weapons still used by some traditional styles are the large Dadao or Ta Tao (大刀) and Pudao or P'u Tao (撲刀) sabres, halberd (jǐ 戟), cane, rope-dart, three sectional staff, Wind and fire wheels, lasso, whip, chain whip and steel whip.

- Two-person tournament sparring (as part of push hands competitions and/or sanshou 散手);

- Breathing exercises; nei kung (內功 nèigōng) or, more commonly, ch'i kung (氣功 qìgōng) to develop ch'i (氣 qì) or "breath energy" in coordination with physical movement and post standing or combinations of the two. These were formerly taught only to disciples as a separate, complementary training system. In the last 60 years they have become better known to the general public.

Modern tai chi

With purely a health emphasis, Tai chi classes have become popular in hospitals, clinics, community and senior centers in the last twenty years or so, as baby boomers age and the art's reputation as a low stress training for seniors became better known.[11][12]As a result of this popularity, there has been some divergence between those who say they practice tai chi primarily for self-defense, those who practice it for its aesthetic appeal (see wushu below), and those who are more interested in its benefits to physical and mental health. The wushu aspect is primarily for show; the forms taught for those purposes are designed to earn points in competition and are mostly unconcerned with either health maintenance or martial ability. More traditional stylists believe the two aspects of health and martial arts are equally necessary: the yin and yang of tai chi chuan. The tai chi "family" schools therefore still present their teachings in a martial art context, whatever the intention of their students in studying the art.[13]

Along with Yoga, tai chi is one of the fastest growing fitness and health maintenance activities in the United States.[12]

Tai chi as sport

In order to standardize tai chi chuan for wushu tournament judging, and because many of the family tai chi chuan teachers had either moved out of China or had been forced to stop teaching after the Communist regime was established in 1949, the government sponsored the Chinese Sports Committee, who brought together four of their wushu teachers to truncate the Yang family hand form to 24 postures in 1956. They wanted to retain the look of tai chi chuan but create a routine that was less difficult to teach and much less difficult to learn than longer (generally 88 to 108 posture), classical, solo hand forms. In 1976, they developed a slightly longer form also for the purposes of demonstration that still didn't involve the complete memory, balance and coordination requirements of the traditional forms. This was the Combined 48 Forms that were created by three wushu coaches, headed by Professor Men Hui Feng. The combined forms were created based on simplifying and combining some features of the classical forms from four of the original styles; Chen, Yang, Wu, and Sun. As tai chi again became popular on the mainland, more competitive forms were developed to be completed within a six-minute time limit. In the late-1980s, the Chinese Sports Committee standardized many different competition forms. They developed sets to represent the four major styles as well as combined forms. These five sets of forms were created by different teams, and later approved by a committee of wushu coaches in China. All sets of forms thus created were named after their style, e.g., the Chen Style National Competition Form is the 56 Forms, and so on. The combined forms are The 42 Form or simply the Competition Form. Another modern form is the 67 movements Combined Tai-Chi Chuan form, created in the 1950s, it contains characteristics of the Yang, Wu, Sun, Chen and Fu styles blended into a combined form. The wushu coach Bow Sim Mark is a notable exponent of the 67 Combined.These modern versions of tai chi chuan (sometimes listed using the pinyin romanization Tai ji quan) have since become an integral part of international wushu tournament competition, and have been featured in several popular Chinese movies starring or choreographed by well known wushu competitors, such as Jet Li and Donnie Yen.

In the 11th Asian Games of 1990, wushu was included as an item for competition for the first time with the 42 Form being chosen to represent tai chi. The International Wushu Federation (IWUF) applied for wushu to be part of the Olympic games, but will not count medals.[14]

Practitioners also test their practical martial skills against students from other schools and martial arts styles in pushing hands and sanshou competition.

Health benefits

Before tai chi's introduction to Western students, the health benefits of tai chi chuan were largely explained through the lens of traditional Chinese medicine, which is based on a view of the body and healing mechanisms not always studied or supported by modern science. Today, tai chi is in the process of being subjected to rigorous scientific studies in the West.[15] Now that the majority of health studies have displayed a tangible benefit in some areas to the practice of tai chi, health professionals have called for more in-depth studies to determine mitigating factors such as the most beneficial style, suggested duration of practice to show the best results, and whether tai chi is as effective as other forms of exercise.[15]Chronic conditions

Researchers have found that intensive tai chi practice shows some favorable effects on the promotion of balance control, flexibility, cardiovascular fitness and reduced the risk of falls in both healthy elderly patients,[16] and those recovering from chronic stroke,[17], heart failure, high blood pressure, heart attacks, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's, and Alzheimer's. Tai chi's gentle, low impact movements burn more calories than surfing and nearly as many as downhill skiing.[18]Tai chi, along with yoga, has reduced levels of LDLs 20–26 milligrams when practiced for 12–14 weeks.[19] A thorough review of most of these studies showed limitations or biases that made it difficult to draw firm conclusions on the benefits of tai chi.[15] A later study led by the same researchers conducting the review found that tai chi (compared to regular stretching) showed the ability to greatly reduce pain and improve overall physical and mental health in people over 60 with severe osteoarthritis of the knee.[20] In addition, a pilot study, which has not been published in a peer-reviewed medical journal, has found preliminary evidence that tai chi and related qigong may reduce the severity of diabetes.[21]

A recent study evaluated the effects of two types of behavioral intervention, tai chi and health education, on healthy adults, who after 16 weeks of the intervention, were vaccinated with VARIVAX, a live attenuated Oka/Merck Varicella zoster virus vaccine. The tai chi group showed higher and more significant levels of cell-mediated immunity to varicella zoster virus than the control group which received only health education. It appears that tai chi augments resting levels of varicella zoster virus-specific cell-mediated immunity and boosts the efficacy of the varicella vaccine. Tai chi alone does not lessen the effects or probability of a shingles attack, but it does improve the effects of the varicella zoster virus vaccine.[22]

Stress and mental health

There have also been indications that tai chi might have some effect on noradrenaline and cortisol production with an effect on mood and heart rate. However, the effect may be no different than those derived from other types of physical exercise.[23] In one study, tai chi has also been shown to reduce the symptoms of Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in 13 adolescents. The improvement in symptoms seem to persist after the tai chi sessions were terminated.[24]In June, 2007 the United States National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine published an independent, peer-reviewed, meta-analysis of the state of meditation research, conducted by researchers at the University of Alberta Evidence-based Practice Center. The report reviewed 813 studies (88 involving Tai Chi) of five broad categories of meditation: mantra meditation, mindfulness meditation, yoga, Tai Chi, and Qi Gong. The report concluded that "[t]he therapeutic effects of meditation practices cannot be established based on the current literature," and "[f]irm conclusions on the effects of meditation practices in healthcare cannot be drawn based on the available evidence.[25]

The Online Tai Chi & Health Information Center funded by the U.S. Government

In 2003, the National Library of Medicine, the largest medical library in the world and subdivision of U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, awarded a grant to build a website titled "The Tai Chi & Consumer Health Information Center". The information center was officially released in 2004 and has since then been providing scientific, reliable and comprehensive information about various health benefits of Tai Chi - for arthritis, diabetes, fall prevention, pain reduction, mental health, cardiovascular diseases, fitness and general well being.[26]Tai chi chuan in fiction

- Tai chi and neijia in general play a large role in many wuxia novels, films, and television series; among which are Yuen Wo Ping's Tai Chi Master starring Jet Li, and the popular Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. A movie that features a traditional tai chi chuan teacher as the lead character is Pushing Hands, Ang Lee's first western film. Internal concepts may even be the subject of parody, such as in Shaolin Soccer and Kung Fu Hustle. Fictional portrayals often refer to Zhang Sanfeng and the Taoist monasteries on Wudangshan.

- Tai chi plays a role in the book series the Five Ancestors as a Chinese Workout that many people do, especially elderly citizens.

- Tai Chi is the basis for the art of Waterbending in the animated television series Avatar: The Last Airbender.

- Tres Navarre the detective in the popular mystery novels by Rick Riordan is a Tai chi master.

Tai chi chuan in modern idiom

Mainly in China, Taiwan and Singapore, and perhaps in other parts of the world where there are large communities of various ethnic Chinese groups, the idiomatic expression 'to play taiji', is used to refer to people trying to politely push or divert responsibility away from themselves.

Label

- Alkitab (5)

- anime (14)

- Arti nama (3)

- Automotif (138)

- Award (1)

- Bahaya (1)

- Bangunan Unik (8)

- belajar html (1)

- benda (24)

- Binatang (36)

- Biografi (81)

- Biologi (6)

- buah (12)

- cara belajar (2)

- CIA (1)

- Community (2)

- contact (1)

- Daerah (18)

- Dewa (2)

- Dijual (1)

- Download software (5)

- drift (1)

- Ekonomi (1)

- FBI (1)

- film (33)

- Fisika (11)

- Game (37)

- ganti kusor blog (1)

- Geografi (27)

- hacker (7)

- Hewan Punah (5)

- Ilmu (48)

- ilmu Beladiri (4)

- Istilah (5)

- kata kata bijak (2)

- kata2 bijak (1)

- Kecepatan (14)

- kimia (1)

- kisah nyata (6)

- Komputer (7)

- Kristen (4)

- kuno (6)

- LAPD (1)

- link (2)

- lirik lagu (3)

- membuat virus (1)

- membuat virus melalui notepad (1)

- membuat virus via notepad (1)

- Misteri (67)

- Misteri dunia (51)

- Mitos (10)

- NASA (88)

- negara (5)

- Organisasi (2)

- Parkour (1)

- Pelajaran (1)

- Perjalanan (1)

- Perkembangan (2)

- petshop (9)

- petugas (1)

- PKN (3)

- pohon (5)

- Puisi (1)

- pulau (9)

- Rahasia (1)

- rubic (2)

- Saion (1)

- sastra (3)

- sejarah (29)

- Senjata (73)

- situs populer (7)

- Sniper (1)

- tata surya (27)

- Teknik (15)

- telepati (1)

- Tenga dalam (1)

- the power of kepepet (1)

- The Three Kingdom (8)

- TIps Binatang (10)

- Tips blogger (4)

- tradisi (9)

- tragedi (4)

- trick magic (2)

- Tumbuhan (1)

- UFO (1)

- Yesus (2)

Loading

Tian's Fan Box

Tian on Facebook

Copyright 2010 Tian

Theme designed by Lorelei Web Design

Blogger Templates by Blogger Template Place | supported by One-4-All

0 komentar:

Posting Komentar